A parallel legal universe, open only to corporations and largely

invisible to everyone else, helps executives convicted of crimes escape

punishment. Part one of a BuzzFeed News investigation — read the whole series here.

Imagine a private, global super court that empowers corporations to bend countries to their will.

Say a nation tries to prosecute a corrupt CEO or ban dangerous pollution. Imagine that a company could turn to this super court and sue the whole country for daring to interfere with its profits, demanding hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars as retribution.

Imagine that this court is so powerful that nations often must heed its rulings as if they came from their own supreme courts, with no meaningful way to appeal. That it operates unconstrained by precedent or any significant public oversight, often keeping its proceedings and sometimes even its decisions secret. That the people who decide its cases are largely elite Western corporate attorneys who have a vested interest in expanding the court’s authority because they profit from it directly, arguing cases one day and then sitting in judgment another. That some of them half-jokingly refer to themselves as “The Club” or “The Mafia.”

And imagine that the penalties this court has imposed have been so crushing — and its decisions so unpredictable — that some nations dare not risk a trial, responding to the mere threat of a lawsuit by offering vast concessions, such as rolling back their own laws or even wiping away the punishments of convicted criminals.

This system is already in place, operating behind closed doors in office buildings and conference rooms in cities around the world. Known as investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS, it is written into a vast network of treaties that govern international trade and investment, including NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Congress must soon decide whether to ratify.

These trade pacts have become a flashpoint in the US presidential campaign. But an 18-month BuzzFeed News investigation, spanning three continents and involving more than 200 interviews and tens of thousands of documents, many of them previously confidential, has exposed an obscure but immensely consequential feature of these trade treaties, the secret operations of these tribunals, and the ways that business has co-opted them to bring sovereign nations to heel.

The BuzzFeed News investigation explores four different aspects of ISDS. In coming days, it will show how the mere threat of an ISDS case can intimidate a nation into gutting its own laws, how some financial firms have transformed what was intended to be a system of justice into an engine of profit, and how America is surprisingly vulnerable to suits from foreign companies.

The series starts today with perhaps the least known and most jarring revelation: Companies and executives accused or even convicted of crimes have escaped punishment by turning to this special forum. Based on exclusive reporting from the Middle East, Central America, and Asia, BuzzFeed News has found the following:

- A Dubai real estate mogul and former business partner of Donald Trump was sentenced to prison for collaborating on a deal that would swindle the Egyptian people out of millions of dollars — but then he turned to ISDS and got his prison sentence wiped away.

- In El Salvador, a court found that a factory had poisoned a village — including dozens of children — with lead, failing for years to take government-ordered steps to prevent the toxic metal from seeping out. But the factory owners’ lawyers used ISDS to help the company dodge a criminal conviction and the responsibility for cleaning up the area and providing needed medical care.

- Two financiers convicted of embezzling more than $300 million from an Indonesian bank used an ISDS finding to fend off Interpol, shield their assets, and effectively nullify their punishment.

ISDS is basically binding arbitration on a global scale, designed to settle disputes between countries and foreign companies that do business within their borders. Different treaties can mandate slightly different rules, but the system is broadly the same. When companies sue, their cases are usually heard in front of a tribunal of three arbitrators, often private attorneys. The business appoints one arbitrator and the country another, then both sides usually decide on the third together.

Conceived of in the 1950s, the system was intended to benefit both developing nations and the foreign companies that sought to invest in them. The companies would gain a fair, neutral referee if a rogue regime seized their property or discriminated against them in favor of domestic companies. And the countries would gain the roads or hospitals or industries that those foreign corporations would, as a result, feel confident building.

“It works,” said Charles Brower, a longtime ISDS arbitrator. “Like any system of law, there will be disappointments; you’re dealing with human systems. But this system fundamentally produces as good justice as the federal courts of the United States.”

Charles Brower Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

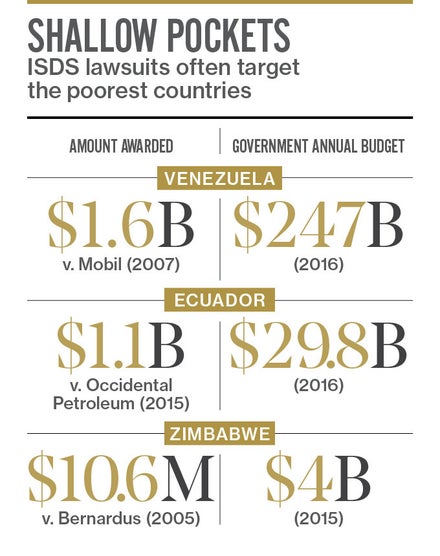

As proof that ISDS delivers justice, Brower pointed to a wave of nationalizations by the Venezuelan government, many while Hugo Chávez was in charge, that led to “huge awards against them for uncompensated expropriation.”

ISDS has not only put rapacious leaders on notice, its defenders say, but it has also encouraged investment, especially in poor countries, helping to raise overall economic development. Some even say that it helps avoid gunboat diplomacy and tense international showdowns because countries have agreed on a forum where they can resolve disputes involving major investments.

But over the last two decades, ISDS has morphed from a rarely used last resort, designed for egregious cases of state theft or blatant discrimination, into a powerful tool that corporations brandish ever more frequently, often against broad public policies that they claim crimp profits.

Because the system is so secretive, it is not possible to know the total number of ISDS cases, but lawyers in the field say it is skyrocketing. Indeed, of the almost 700 publicly known cases across the last half century, more than a tenth were filed just last year.

ISDS has morphed from a rarely used last resort into a powerful tool that corporations brandish ever more frequently.

A few of their ideas: Sue Libya for failing to protect an oil facility during a civil war. Sue Spain for reducing solar energy incentives as a severe recession forced the government to make budget cuts. Sue India for allowing a generic drug company to make a cheaper version of a cancer drug.

In a little-noticed 2014 dissent, US Chief Justice John Roberts warned that ISDS arbitration panels hold the alarming power to review a nation’s laws and “effectively annul the authoritative acts of its legislature, executive, and judiciary.” ISDS arbitrators, he continued, “can meet literally anywhere in the world” and “sit in judgment” on a nation’s “sovereign acts.”

That fate has not yet befallen the United States — but largely because of sheer luck, former government lawyers said. In theory, ISDS arbitrators must follow the rules laid down in trade pacts. But in practice, they have interpreted the vague language of many treaties as enshrining broad, unwritten rights far beyond protections against property seizures and blatant discrimination — even finding, in one case, a right to a “reasonable rate of return.”

Some entrepreneurial lawyers scout for ways to make money from ISDS. Selvyn Seidel, an attorney who represented clients in ISDS suits, now runs a specialty firm, one that finds investors willing to fund promising suits for a cut of the eventual award. Some lawyers, he said, monitor governments around the world in search of proposed laws and regulations that might spark objections from foreign companies. “You know it’s coming down the road,” he said, “so, in that year before it’s actually changed, you can line up the right claimants and the right law firms to bring a number of cases.”

The US officials who negotiated the Trans-Pacific Partnership have argued that it contains new ISDS safeguards, including opening up hearings and legal filings to the public. The changes, however, have loopholes, and lawyers at some big firms are already advising clients how they might use the new deal to their benefit.

Opposition to ISDS is spreading across the political spectrum, with groups on the left and right attacking the system. Around the world, a growing number of countries are pushing for reforms or pulling out entirely. But most of the alarm has been focused on the potential use of ISDS by corporations to roll back public-interest laws, such as those banning the use of hazardous chemicals or raising the minimum wage. The system’s usefulness as a shield for the criminal and the corrupt has remained virtually unknown.

Reviewing publicly available information for about 300 claims filed during the past five years, BuzzFeed News found more than 35 cases in which the company or executive seeking protection in ISDS was accused of criminal activity, including money laundering, embezzlement, stock manipulation, bribery, war profiteering, and fraud.

Among them: a bank in Cyprus that the US government accused of financing terrorism and organized crime, an oil company executive accused of embezzling millions from the impoverished African nation of Burundi, and the Russian oligarch known as “the Kremlin’s banker.”

Some are at the center of notorious scandals, from the billionaire accused of orchestrating a massive Ponzi scheme in Mauritius to multiple telecommunications tycoons charged in the ever-widening “2G scam” in India, which made it into Time magazine’s top 10 abuses of power, alongside Watergate. The companies or executives involved in these cases either denied wrongdoing or did not respond to requests for comment.

Most of the 35-plus cases are still ongoing. But in at least eight of the cases, bringing an ISDS claim got results for the accused wrongdoers, including a multimillion-dollar award, a dropped criminal investigation, and dropped criminal charges. In another, the tribunal has directed the government to halt a criminal case while the arbitration is pending.

“You have a lot of scuzzy sort-of thieves for whom this is a way to hit the jackpot.”

Lawyers say that some governments, faced with a legitimate ISDS claim, will even trump up a criminal charge to deflect from their own wrongdoing. For example, arbitrators found there was evidence suggesting that Bolivia had launched a fraud case against mining-company executives as a ploy to get the company’s ISDS claim thrown out.

But even some members of The Club said they were concerned by how often credible allegations of criminality arise. Many ISDS lawyers say that the system helps promote the rule of law around the world. If ISDS is seen as protecting criminals, they fear, it could delegitimize a system that is working well for many others.

One lawyer who regularly represents governments said he’s seen evidence of corporate criminality that he “couldn’t believe.” Speaking on the condition that he not be named because he’s currently handling ISDS cases, he said, “You have a lot of scuzzy sort-of thieves for whom this is a way to hit the jackpot.”

Even in the world of ostentatious opulence that Dubai real estate moguls inhabit, Hussain Sajwani and his company, Damac Properties, stand out. His promotions are gaudy — buy an apartment, get a Jaguar. He’s partnered with Donald Trump on a golf course for a Damac resort in Dubai. He’s raffled off a private jet and a private Caribbean island.

In the midst of his meteoric rise, he began looking beyond the oil-rich United Arab Emirates and, in 2006, ventured into an attractive new market: Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt. Top officials from the notoriously corrupt regime, including the prime minister, traveled to Dubai and cemented the new partnership with a signing ceremony for a splashy deal.

Hosni Mubarak Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

Egypt was in tumult, with the military controlling the government, frequent protests still roiling the streets, and the Muslim Brotherhood jockeying for what would become its electoral victory. Criminal trials in Egypt were often still gravely flawed, and corporate lawyers in Cairo said the military government was pursuing corruption trials to placate protesters and settle political scores. But anticorruption fervor had helped fuel the occupation of Tahrir Square, and to some activists and ordinary Egyptians, this once unthinkable verdict signaled that the elites who had enriched themselves through sweetheart deals with the regime might no longer be above the law.

But then some of those elites wielded a new weapon: ISDS. One of the first to do so was Sajwani.

The son of a disciplinarian shop owner in Dubai, Sajwani had rebelled against his conservative father and eventually found his way to the United States, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Washington. Back in the United Arab Emirates, he sold timeshares and started a catering company.

By 2002, he’d determined the real money was in real estate, and he founded Damac Properties. The company quickly asserted itself as a major player in the booming Dubai property market and began expanding abroad.

Hussain Sajwani Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

At the time Sajwani bought into Egypt, corruption was costing the nation about $6 billion every year, according to an analysis by Global Financial Integrity, a nonprofit based in Washington, DC, that tracks illegal financial flows. Meanwhile, hospitals and schools deteriorated; unemployment soared; and about 1 in 5 Egyptians got by on less than $2 a day, according to the World Bank. By some estimates, the majority of Cairo’s roughly 17 million citizens languished in “informal housing” — slipshod buildings or fetid slums, largely cut off from basic services such as water and electricity.

Amidst this squalor, verdant billboards selling Sajwani’s lavish properties emerged from the city’s oppressive sand-tinted haze. “It was clear and obvious, in your face on a daily basis,” said Maher Hamoud, who was editor-in-chief of a major Egyptian newspaper at the time. “Everyone saw these billboards, and everyone knew of this parallel world that the majority of the population have no access to.”

Sajwani’s first project wasn’t going to be just a luxury resort. He would build the Middle East’s largest tourist paradise — 11 square miles of villas, shopping centers, apartments, marinas, and even an extreme sports theme park, all along the sunny coastline of the Red Sea, a popular haven for foreign vacationers and rich Egyptians. Soon, those who could afford it would be able to “Live the Luxury” — Damac’s slogan — just a few hours’ drive from Cairo.

But when Hamoud’s newspaper asked what Damac had paid for this huge stretch of land, which previously had belonged to the Egyptian people, a company executive refused to answer. “Invasion of privacy is unacceptable,” he said, “and we are a private company.”

Zuhair Garana Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

Almost five years later, Damac still hadn’t built the resort, nor had it fully paid Egypt even that bargain-basement price, prosecutors’ files show.

In March 2011, shortly after the revolution felled Mubarak, prosecutors accused Sajwani and Garana of collaborating on the deal, which would cheat the Egyptian people out of about $41 million. What’s more, prosecutors alleged, the land on the Red Sea sat atop an oil deposit, so it was illegal under Egyptian law to sell the area as a tourism project. Through his lawyers, Sajwani has maintained he did nothing wrong.

Two months later, an Egyptian court found Sajwani and Garana guilty on corruption-related charges. (A court would later vacate Garana’s conviction.) A judge ordered Sajwani, who had not returned to Egypt for the trial, to forfeit the land, pay a penalty, and serve a five-year prison sentence.

The verdict rippled through the business community, stoking anxiety, according to a half-dozen corporate lawyers in Cairo. Many other businesses had cut land deals in the frenzied sell-off of once-public assets during the past decade, and they wondered if they might be next.

Sajwani himself had two other projects planned in Egypt — an exclusive gated community named Hyde Park and an upscale shopping mall dubbed Park Avenue — and authorities were investigating those, too, previously secret documents show. In these deals, authorities alleged in the documents, Sajwani worked with the housing minister, improperly reaped the equivalent of about a half-billion dollars by selling units earlier than allowed, funneled the money abroad using a web of holding companies, and still failed to pay the government the full amount owed for the land. Sajwani was never charged in relation to this investigation.

But, though Mubarak was gone, he had left behind a gift for investors like Sajwani: one of the world’s largest networks of investment treaties — twice the size of the United States’ — that allowed foreign businesses to file ISDS claims against Egypt. Within a week of Sajwani’s conviction over the Red Sea deal, Damac invoked one of these treaties and sued Egypt before the international arbitration arm of the World Bank.

The company announced the case with a defiant statement from one member of the powerhouse legal team it had assembled — an American who’d started his career as the youngest Republican state legislator in Texas.

“The criminal prosecution and conviction of Mr. Sajwani were a classic case of guilt by association,” wrote Ken Fleuriet, of the US firm King & Spalding. “No crime was committed by simply conducting business with the former regime.” The deal, he said, was “entirely proper” and “fully vetted by the appropriate Egyptian officials at the time of purchase.” Fleuriet did not respond to requests for comment. (A different law firm, the London-based Clifford Chance, later took over the case.)

This argument — that the government at the time gave its blessing, so the sweetheart deal couldn’t be criminal — became the template for other businesses facing similar accusations.

Sue Ellen, a native Egyptian named after the matriarch on the TV show Dallas, started working for Damac as its in-house counsel in Egypt after the land deal that resulted in Sajwani’s legal troubles. She resigned after only a year because, she said, she was uncomfortable with some company practices. When questioned about the Red Sea deal, she said, “I haven’t asked,” and said she doesn’t know any of its details. But she wrote her master’s thesis on Egypt’s rampant white-collar crime.

Speaking generally, she said, “They are very, very, very smart — the investors and the government.” She gave an example of how bribery can go undetected: “I provide you with a villa, a townhouse, but not in your name. The name will be someone else, but you will be the beneficiary.” She ticked off other common ploys: “It could be Rolex watches, free apartments. If you have a son, he could work” at the company “with a huge amount of salary. So it’s not only bribery. Sometimes you goof around the bribery and do something not visible.”

By filing an ISDS claim, Sajwani took his case out of the Egyptian court system and placed it in the hands of three private lawyers convening in Paris. For the arbitrator he was entitled to choose, Sajwani appointed a prominent American lawyer who had often represented businesses in ISDS cases. And to press his case, Sajwani hired some of the world’s best ISDS attorneys.

For Egypt, the potential losses were big and would come as the country struggled to revive its floundering economy.

The man who had been convicted of collaborating on a deal that would bilk the Egyptian people out of millions of dollars was now free and clear.

The terms of the settlement are confidential, but three lawyers who represented the company at the time described the key provisions. Damac paid some money to the government; Sajwani’s lawyers refused to say how much, though one called it a “savvy business deal.”

But the key benefit for Sajwani, according to all three: In exchange for dropping his ISDS case, Egypt would wipe away his five-year prison sentence and close out the probes of the other deals. The man who had been convicted of collaborating on a deal that would bilk the Egyptian people out of millions of dollars was now free and clear.

A Damac spokesperson declined to make Sajwani available for an interview. In response to a letter detailing the points in this story, the spokesperson wrote: “This story relates to issues that were resolved and settled in 2013. The assertions you make in your letter are factually wrong. As the matter was the subject of formal settlement, we are not in a position to comment any further.” Asked which facts were wrong, the spokesperson declined to answer.

The Damac case — one of the first post-revolution criminal convictions and one of the first ISDS claims filed as a result — set an example that other embattled executives soon followed. As Egypt groped for stability, a wave of ISDS claims rattled the new government.

“Damac, followed by multiple other cases filed, made them say, ‘You know what, no; there should be another way,’” said Girgis Abd el-Shahid, a lawyer who represents corporate clients and assisted with Sajwani’s arbitration claim. “I believe that, after Damac, Egypt learned its lesson.”

By the one-year anniversary of the revolution, Egypt faced more known ISDS claims than all but a handful of other countries, and corporate lawyers in Cairo told BuzzFeed News that still more businesses were threatening to file cases.

The potential liabilities from these claims were ruinous — one company alone was threatening to sue for $8 billion. What’s more, the ISDS cases were helping to sour the country’s business reputation at a time when the fragile Egyptian economy desperately needed foreign investment.

Virtually across the board, the government began trying to settle.

In one case, an Egyptian court had declared a foreign company’s purchase of a factory corrupt and nullified the deal, court records show. But after the company filed an ISDS claim, the government agreed to pay $54 million in a settlement — roughly twice the price the company had paid for the factory just a few years earlier, according to news reports and documents reviewed by BuzzFeed News. A lawyer for the company said that his client had not been found guilty of a crime and that the company had made “significant investments” in the factory after acquiring it.

In another case, a second Dubai developer was under investigation — until he threatened an ISDS claim, according to the Cairo lawyer Hani Sarie-Eldin, who has represented the company. Instead of a criminal trial, the government opted for a settlement, and the mogul’s company went forward with its project, Sarie-Eldin said.

Other ISDS cases are ongoing. Two involve a notorious deal that sent Egyptian natural gas to Israel, even as Egyptians suffered energy shortages at home. Egypt asked ISDS arbitrators to throw out both cases, alleging that the deal was a corrupt arrangement by Mubarak-regime officials and cronies to reap huge profits. In both cases, the request was denied. Investors in the gas company, like the Dubai developer, did not respond to requests for comment.

A Cairo street with luxury apartments in the background. Sima Diab for BuzzFeed News

One purpose of the law, according to corporate lawyers in Cairo who said they lobbied for it, was to prevent the domestic court cases that had led to ISDS claims. As a result, several cases challenging Mubarak-era deals are now frozen.

Corporate lawyers cheered these developments. But even some supporters of ISDS now worry that the system has been misused to help the powerful evade justice and to hold hostage the economy of a nation still in turmoil.

“If you get something out of corruption, you should not have your day in court; it should be dismissed,” said Ahmed el-Kosheri, a native Egyptian and longtime arbitrator who recently received a lifetime achievement award from a leading international arbitration organization.

He worried that his country would be saddled with massive costs because of the ISDS cases. “That’s the irony of it,” he said, “that innocent people, the Egyptian public, would pay for the mistakes committed by the regime, which was corrupt.”

Since settling with Egypt, Sajwani has enticed customers elsewhere with free Lamborghinis; partnered with Trump, whose campaign did not respond to requests for comment, on a collection of luxury mansions; and sold Damac shares on the London Stock Exchange, reaping a windfall.

“If we try to expose corruption, then those investors will take us to court,” she said. “Which means we had better just shut up.”

Sajwani is now advertising a massive tower in London with apartments designed by Versace Home, and he told an Emirati newspaper he’s eyeing continued expansion; next might be projects in the United States.

Heba Khalil, a researcher at an Egyptian human rights organization, recently recalled the chaotic but hopeful days after the fall of Mubarak. “No one knew what Egypt would be like,” she said. “International investors were kind of scared that the kind of deals that they did with the Mubarak regime wouldn’t be possible anymore.”

Then came the ISDS claims. “I think the impact of international arbitration,” Khalil said, was that Egyptians “started knowing that, ‘Oops, if we try to expose corruption, then those investors will take us to court internationally, and we will lose the case. Which means we had better just shut up and let the wrongs of Mubarak continue the way they are.’”

Six days earlier, César had suddenly collapsed and died. He was a healthy 16-year-old, she said, except for one thing: the lead in his body.

He’d complained of unceasing pain in his head, chest, stomach, and bones, she said, and he grew fatigued easily — all common symptoms of lead poisoning. The concentration of lead in César’s blood, a test had shown, exceeded the level internationally recognized to cause serious health problems.

“Imagine,” Hernández recalled César saying after a doctor explained what the results meant, “I’m the youngest son you have, and I’m going to die soon.”

Not far away, across the street from the village school, Fany Carolina held an X-ray up to the light streaming through her kitchen window and pointed to dark spots on the images of her son José’s leg bones. These, she said doctors told her, likely were deposits of lead. She unfolded reports showing levels of lead in her son’s blood above the safe limit. The hazardous metal had first appeared in his body when he was 5 years old. Eight years later, he has pain in his joints, and Carolina worries his development has been stunted.

René Colocho speaks about his daughter Ángela, who died in 2013. Juan Carlos for BuzzFeed News

Sitio del Niño is a manmade disaster, a result of environmental neglect by the lead-acid battery factory nearby, legal documents show.

Not long after the battery factory set up shop on the edge of Sitio del Niño in 1998, people began noticing clouds of ash floating over from their new neighbor, descending on fields where children played soccer and seeping into their homes at night. It burned people’s throats and sent them into coughing fits.

Eventually, people started connecting the ash with the persistent headaches, dizziness, extreme fatigue, and constant bone and joint pain that children in particular were suffering. In 2004, a committee of local citizens began petitioning leaders for help, writing the town’s mayor, national government ministries, and eventually even other nations’ embassies and international aid organizations. For years, their efforts came to naught.

Then lead started showing up at potentially dangerous levels in the blood of the town’s children. Testing in 2006 and 2007 found that dozens of children, some as young as 3, had been contaminated.

Testing found that dozens of children, some as young as 3, had been contaminated.

Angry parents and a legal aid group demanded that the government take action. In 2007, the health ministry ordered the closing of the factory on the grounds that it lacked the proper permits. The following year, the attorney general brought charges of aggravated environmental pollution against the company, its three owners, and three lower-level managers.

The factory’s owners, members of a prominent family in El Salvador who also hold US citizenship, fled to the US, which was asked to extradite two of them. The US refused, on the grounds that environmental crimes are not covered under the US–El Salvador extradition treaty.

In an email to BuzzFeed News, José Gurdian, the company’s president, vehemently denied wrongdoing and insisted that his factory had been “confiscated by the government of El Salvador in violation of all local and international law.” No test results ever showed that the factory was “emitting lead into the air,” he said, and his company had “made all the necessary investments” to meet the safeguards that environmental regulators required. He disputed tests conducted before the factory closed that found lead contamination, and he said that the government’s closure process itself “could have caused limited pollution.” (The factory’s other two owners are Gurdian’s mother, Sandra Escapini, who directed questions to her son, and another relative, Ronald Lacayo, who did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.)

They were safe in Florida, and the case against them did not proceed. But the case against their company and three of its managers did. Before long, the company’s legal team turned to ISDS.

The bus stop in front of the battery factory with graffiti painted by community activists: “LIFE, HEALTH,” “RIGHTS.” Juan Carlos for BuzzFeed News

Gurdian, the company president, told BuzzFeed News the ISDS threat was not intended to help the criminal case. The architects of his company’s legal defense, however, said it was a key prong of their strategy. Arturo Girón, the lead criminal defense lawyer, said it was “necessary to strengthen” their case. In talks with the government, he said, he warned that the company might “play that card” if the case could not be resolved.

Another factory lawyer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that the threat to sue in ISDS was like a chess move intended to send the government an intimidating message: “I’m not so tiny; I have powerful people behind me.” After the ISDS threat, the government officials’ tone changed. “All of a sudden, they were very, very polite, and careful,” he said.

And Luis Francisco López, a lawyer who represented the community as an interested party in the case, said the ISDS threat came up in meetings he attended involving the attorney general’s office and the factory lawyers. “The message we got from the beginning was, ‘Even if you beat us here, we’re going to beat you there,’” he said.

In the midst of the trial, the prosecution agreed to settle. Prosecutors declined to comment on the role ISDS played, but the settlement document lays out the terms. The company agreed to pay for a limited cleanup of only the factory site, far short of the much more expansive cleanup the government has said is needed, and to establish a medical clinic in the village, albeit one that would provide only basic care and be funded for only three years. The company would also pay for some of the costs associated with the prosecution and make small donations to the community. And it agreed to drop its threat and not pursue an ISDS case.

Lawyers for the community denounced the deal, saying it failed to address the community’s problems. The judges also refused to sign off on the prosecutor’s bid to end the case, instead carrying it to its conclusion.

Ultimately, the court concluded that the factory had contaminated the village. But that same court acquitted the three lower-level managers, so, it reasoned, it had no choice but to exonerate the company, too.

A force that helped persuade the judges, said Girón, the company’s lawyer, was the ISDS threat and its potential to slam the government with huge compensatory damages.

Today, the legal wrangling — and the possibility of an ISDS claim — persists.

The factory is pursuing an administrative case against the government, and prosecutors have filed a new criminal case, accusing the owners of causing physical harm to the villagers. Gurdian dismissed the new charges as “completely baseless.” But they might leave him and the other two owners vulnerable to extradition. If prosecutors do try to pursue the owners abroad, the factory lawyer said he knew exactly what move he would recommend: an ISDS claim.

The failure to hold the factory accountable is an open wound for the impoverished residents of Sitio del Niño — a village whose very name, “Place of the Child,” is now a cruel joke. For six years, their community has been designated an “environmental emergency” by the government, which has warned them not to eat anything grown in the town’s contaminated soil. But many of them have no other option.

The government has estimated that the total cost to remove the lead from the area and to restore the land would be about $4 billion. “We have a solution,” the environmental minister, Lina Pohl, told BuzzFeed News. But, she said, “We are waiting for someone to give us the money.”

Meanwhile, Rosa Aminta Rodríguez de Morales is waiting to find out how dire her son’s health is. When she gave birth to Luis Jr., now 14, a doctor told her, “Don’t have any other children until the factory closes,” she recalled.

In 2007, when Luis Jr. was 5, tests showed unsafe levels of lead in his blood. He has suffered dizziness, extreme fatigue, and pain in his joints and bones.

Recently, his dizzy spells seemed to be getting worse, so his parents saved enough money from selling homemade cheese to take him to a private clinic. Doctors ran tests that indicated he had kidney disease — a classic symptom of lead poisoning.

The toxic metal is known to strike multiple organs, and Rodríguez and her husband said they hoped to save enough over the next month to find out whether their son’s liver was also failing.

“Psychologically,” Rodríguez said, “he already feels like he’s going to die.”

When NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, took effect in 1994, some lawyers at top firms took notice of ISDS for the first time. One heralded “a new territory” where some pioneering attorneys had ventured and “prepared maps showing a vast continent beyond.” What they saw was the opportunity to expand and reshape ISDS to their benefit, and the previously dormant system changed forever.

“A whole industry grew up,” said Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah, an international lawyer and ISDS arbitrator who argued that the system is now being misused. Large law firms, he said, see ISDS “as a lucrative area of practice, so what happens is they think up new ways of bringing cases before the arbitration tribunals.”

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, June 2016

A key service offered by the ISDS legal industry goes by various euphemisms: “corporate structuring,” “re-domiciling,” “nationality planning.” Critics have a different term: “treaty shopping.” It amounts to helping businesses figure out which countries’ treaties afford the most leeway for bringing ISDS claims, then setting up a holding company there — sometimes little more than some space in an office building — from which to launch attacks.

So it is that a private equity firm based in Texas can fly the flags of Belgium and Luxembourg, enabling it to sue South Korea, which convicted one of its executives of stock manipulation. The private equity firm declined to comment.

Source: Investment Policy Hub

ISDS lawyers also grow the market for their services by advocating for new treaties, and some of the most outspoken are beneficiaries of the revolving door between the US government and top law firms.

Daniel M. Price negotiated the section of NAFTA containing ISDS when he was a lawyer at the Office of the US Trade Representative. He later served as a top international trade official in the George W. Bush White House.

Daniel M. Price Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

He founded and chaired the unit handling ISDS claims at Sidley Austin, a leading global law firm. Today, he promotes his services as an arbitrator and, along with a powerhouse team that includes other former government lawyers, sells international expertise on ISDS and related matters.

Price, who at first agreed to an interview but later stopped responding to messages, is only one of a number of private lawyers who have exerted outsize influence on American policy on ISDS.

Ted Posner, a partner at US firm Weil, Gotshal & Manges and a former official at the Office of the US Trade Representative, has acted as a direct conduit to treaty negotiators. As officials from his former employer were hammering out the details of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Posner told BuzzFeed News, he met with them on behalf of his clients and said, “We want you to be aware of this concern and hope that you’ll take this point of view into account in the next round of negotiations.”

“I don’t see that as being a conflict,” Posner said. “I don’t think anybody gives my point of view more credibility just because they happen to have been a former colleague. I may be able to get a call returned more quickly or an email responded to more quickly, but I don’t think prior service in an agency and knowledge of how that agency works is something that should be considered problematic from a public-interest point of view.”

Private attorneys have emerged as some of the staunchest defenders of ISDS, accusing critics — from prominent scholars, to aid groups such as Doctors Without Borders, to the Australian government — of failing to understand the system and making exaggerated claims. While they concede that many arbitrators are chosen from their own ranks, they say that when lawyers adjudicate cases, they weigh the evidence without favor and reach just decisions in the overwhelming majority of cases. Their reputation for fairness is their currency, they say.

To prove that ISDS is not biased in favor of businesses, they point to the outcomes of known cases: Governments have won about 35% of the time, while business interests have won only about 25%.

But that statistic is anything but straightforward. It pertains only to the outcomes of known cases; ISDS is so secretive no one even knows how many additional cases there have been. Also secret are most of the settlements. Roughly a quarter of the known cases were settled, but the terms are almost never disclosed.

Moreover, subtract the cases that arbitrators tossed out because they didn’t have jurisdiction to hear the claim, and that win–loss balance flips: Business interests have won 60% of the time. Even then, cases recorded as losses for the corporation can actually be wins. In one case, an executive failed to garner a monetary judgment but obtained a finding that helped him wipe away a criminal punishment.

And no statistic could ever include the many ISDS claims that are merely threatened, intimidating governments and shaping their policies while leaving hardly a trace. ISDS lawyers told BuzzFeed News that threats far outnumber actual cases.

Finally, companies can gain advantages by bringing an ISDS suit, even if they don’t expect to win the case. Krzysztof Pelc, an associate professor at McGill University, found that there has been a proliferation of frivolous cases primarily intended not to win compensation but rather to bully the government — and other nations that want to avoid a similar suit — into dropping public-interest regulations. These new cases, Pelc found, represent a fundamental transformation of ISDS: The system was designed to deal primarily with theft by autocrats, but, in the majority of cases today, businesses are suing democracies for enacting regulations.

Such cases, he found, are far less likely to end in a settlement; the goal is to draw out the legal fight and run up the government’s cost to deter future regulation. Even when a government ultimately wins, foreign investment in that country drops, another study found.

“The noble intent behind investor-state dispute settlement,” Pelc told BuzzFeed News, is now “a tiny, tiny part of the action.” The system has a legitimate purpose, he said. “It’s just that, when it comes to this kind of use of aggressive litigation, then it really gets away from the objective.”

Not all lawyers involved in ISDS are opposed to reform. Some, in fact, say it is necessary in order to protect the system. Industry publications and conferences now are filled with hand-wringing over the mounting public criticism of ISDS.

V.V. Veeder, a prolific arbitrator, warned fellow ISDS lawyers during a panel discussion at a London law office that, while they might be convinced of the merits of the system, many members of the public are not. “And,” he said, “the more they find out what we do and what we say, and how we say it, the more appalled they are.”

The British financial guru Rafat Ali Rizvi had a big problem: In Indonesia, where he’d plied his trade, he and a business partner had been convicted of embezzling more than $300 million from one of the country’s banks. The government there had to bail out the bank — sparking enraged protests that police tried to quell with tear gas and water cannons — and Indonesian authorities were pursuing him and the money they said he’d stashed in accounts around the world.

Ensconced overseas, Rizvi was beyond the reach of the Indonesian authorities. But the conviction came with an Interpol “red notice,” meaning he risked extradition if he traveled abroad. Some of his bank accounts were frozen. And with this stain on his record, he was largely cut off from the world of global finance he’d played in for years.

Rizvi’s topflight criminal lawyer had threatened to sue Interpol if the agency didn’t delete the alert, but so far it hadn’t worked. What Rizvi needed was an entirely different type of lawyer. Someone like George Burn.

Dita Alangkara / AP

Dita Alangkara / AP

Police and protesters during demonstrations over the bailout of Bank Century.

The strategy he crafted for Rizvi epitomizes the ingenuity of elite ISDS lawyers and the willingness of arbitrators — many of whom are also attorneys who argue ISDS cases — to expand their own authority. It is a stark example of how canny and audacious lawyers can work the system, crafting a win even when they technically lose. The only real losers: a nation of taxpayers.

Born in Pakistan and educated in Great Britain, Rizvi had been managing private investment funds set up in various tax havens when he met Hesham al-Warraq, a Saudi financier educated in the US.

Rafat Ali Rizvi Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

The bank was short on cash. It had a hefty stash of bonds and other securities, but it couldn’t wait for them to pay out. The bank needed the money now.

Rizvi and al-Warraq got approval from the bank’s other executives to sell many of these long-term investments or use them as collateral to obtain loans. Step one was transferring them to offshore companies that Rizvi and al-Warraq controlled.

If there was a step two, it basically never happened; the bank never saw the vast majority of those valuable assets again, legal documents show.

The two men were supposed to return to the bank whatever they couldn’t sell or use to get a loan, but, for the most part, they simply didn’t, according to the documents. In some instances, the documents state, they used the assets to get loans not for the bank but for themselves.

Hesham Al-Warraq Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

Rizvi and al-Warraq contended that they actually had obtained at least a few loans for the bank and that the assets had been seized by creditors after the bank failed to repay these loans. But the bank and the experts hired by the Indonesian government said they couldn’t find any evidence to support that claim.

The Brattle Group analysis summed it up: “Mr. Al Warraq and Mr. Rizvi controlled Bank Century, and treated it as their personal piggybank.”

A criminal court in Jakarta tried them in absentia, convicted both men of corruption and money laundering, sentenced each to 15 years in prison, and ordered them to repay the massive sum it found they’d stolen.

They could have returned to Indonesia and challenged their convictions in court or tried to file a claim with a United Nations human rights body designed to handle the kind of claims they were making. But they had a more attractive option.

Enter Burn. His overarching strategy, as he explained it, was to use ISDS to attack the validity of their Indonesian trial, arguing “that they’d never been given a fair hearing and that there had been an abuse of process at multiple stages.” But to get to that point, he had to deploy some of the most controversial tactics that ISDS lawyers have developed.

First, Burn needed to find a treaty that would apply to this case. His team discovered an obscure agreement among predominantly Islamic nations, including Indonesia, where the case was unfolding, and Saudi Arabia, where al-Warraq was a citizen. There was no record of anyone using that pact to file an ISDS claim before, but Burn audaciously forged ahead.

George Burn Danilo Agutoli for BuzzFeed News

The key argument that Burn planned to make was that the criminal trial in Jakarta had violated al-Warraq’s right to fair treatment as a foreign investor. This protection is now commonplace in investment treaties and trade deals, and it has become one of the most controversial aspects of ISDS.

Guaranteeing foreign businesses “fair and equitable treatment” sounds like common sense. But many treaties don’t say what exactly that means, so arbitrators have found that governments have acted unfairly even when they regulated the price of water or merely complied with European Union law. Critics argue that such judgments have transformed a system that was supposed to uphold the rule of law into one that places foreign businesses above the law, able to get out of obeying almost any statute or regulation, no matter how worthwhile, that cuts into profits.

Many scholars and activists say the “fair and equitable treatment” provision, which is included in the Trans-Pacific Partnership now being considered by Congress, is the most widely abused element of treaties containing ISDS. Numbers from the UN’s trade and development body show that arbitrators find violations of this controversial provision far more than any other.

As it happened, though, the treaty Burn had invoked didn’t include that clause. But the agreement did have another common and often controversial clause, which requires a government to treat foreign businesses covered under one treaty at least as well as businesses covered under any of its other treaties.

So Burn plucked the fair-treatment provision from another agreement and applied it to the Islamic nations pact. In effect, he constructed his own super-treaty.

And the ISDS arbitrators allowed it, giving themselves the authority to rule on the actual merits of the case.

“Mr. Al Warraq and Mr. Rizvi controlled Bank Century, and treated it as their personal piggybank.”

He argued that the Indonesian authorities had committed numerous procedural errors, such as not confirming that al-Warraq had received the court summons and not enlisting the Saudi authorities to question al-Warraq. He also argued that Indonesia hadn’t met the criteria under international law for conducting a trial in absentia and that it hadn’t ensured al-Warraq was promptly notified of the guilty verdict. He even argued that the entire prosecution was a politically motivated ploy to scapegoat Rizvi and al-Warraq for the government’s own contentious decision to bail out the bank.

For its part, the Indonesian government produced evidence that it had done many of the things it was accused of neglecting: It did seek help from the Saudi government, and it did seek out Rizvi and al-Warraq at various locations around the world. What’s more, the government contended, Rizvi and al-Warraq had asked their lawyers to write to government officials, and the men had dispatched representatives to meet with Indonesian authorities as the trial approached. Those actions, the government said, made it clear that Rizvi and al-Warraq knew about the case against them and could have returned to face the court in person, avoiding the trial in absentia, but chose not to do so.

Ultimately, the tribunal did not find that the prosecution had been politically motivated. But siding with Martha and Burn, it did make a key finding: Indonesia had committed procedural errors that violated al-Warraq’s right to fair treatment. The arbitrators didn’t award any money, however, because they also determined that al-Warraq had “breached the local laws and put the public interest at risk.”

But, Burn said, winning the case outright and getting monetary damages had never been the “primary target.” Above all, he said, he wanted a finding that al-Warraq’s rights had been violated. And the ISDS arbitrators handed him exactly that.

Martha took that crucial finding and presented it to his former employer. He argued that, unless Interpol dropped its red alerts against Rizvi and al-Warraq, the international cops themselves would be violating international law. Interpol obliged, deleting the red notices.

“Unprecedented Concessions by Interpol,” trumpeted a press release put out on behalf of Martha’s firm. The international cops also had agreed to delete information about the two convicts from its files and to send letters to certain risk profiling and due diligence agencies, as well as the roughly 190 Interpol member countries, according to the release.

“As a result, Mr. Rizvi and Mr. Al-Warraq will be able to travel and conduct business without restriction,” the release boasted. “Such results have never been obtained before from INTERPOL.” Reached by BuzzFeed News, Martha at first agreed to an interview but didn’t respond to subsequent messages.

Now the legal team is trying to use the ISDS decision to block Indonesia from seizing the men’s foreign bank accounts. Initially, Indonesian authorities had won a small victory when a Hong Kong court granted them access to a $4 million account. But that’s been put in doubt.

“I am trying to bury this part of my life,” al-Warraq wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News.

Legal side skirmishes continue, but Rizvi and al-Warraq have won the war. Rizvi is, for the most part, back to traveling and conducting business, Burn said. Rizvi himself did not respond to detailed questions sent to his email address, hand-delivered to a London home listed in his name, and provided to Burn and other intermediaries.

Al-Warraq has had a much tougher time than Rizvi, Burn said, even though, as “the junior guy,” he “didn’t take any of the commercial decisions.” In addition to the Interpol red notice, Burn said, Indonesia petitioned Saudi Arabia to extradite al-Warraq, then asked Saudi Arabia itself to try him. “Al-Warraq probably for the last four years has had to report to the police every week,” Burn said.

But, he added, the ISDS finding was the key to persuading the Saudi court to finally drop the case.

“I am trying to bury this part of my life,” al-Warraq wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News, but “to this date I am banned and unable to travel from Saudi Arabia.” In reference to a detailed summary of the facts in this story, he said “so many points” are “not correct,” but he did not respond to follow-up questions asking for specifics. Calling himself “wrongly accused,” he said it was “a life mistake I got involved with bank century.”

As for Burn, “I take a great deal of pride in holding states like Indonesia to account for their lack of rule of law,” he said. “There is no meaningful evidence that Rizvi and al-Warraq were involved in any frauds, but, even if they were, the absolutely tainted nature of the process over a number of years means that nobody will ever know.”

But to Cahyo, who said that years of effort by his team haven’t led to the recovery of a single dollar of the bailout money, the ISDS gambit looks rather different.

“They are playing this game as if they are honest investors coming to Indonesia trying to do business,” he said. “That is not the case. This is really somebody robbing the people’s money.” ●

After the bankruptcy that brought in the "New Deal" a new legal system was created right here in America. The Unified Commercial Code or UCC seemed to replace our system of Constitutional law. Instead of Congress creating the laws I have read that lawyers gathered in Chicago to create a legal system for the bankrupt United States. This system was adopted by all the States except Washington D.C. Six weeks after the assassination of JFK Washington D.C. also came on board the new UCC system. Am I mistaken?

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete