Meet the monks who brew the only Trappist beer in America

Every

morning, Isaac Keeley, O.C.S.O., a contemplative Trappist in the autumn

of his days, wakes up at 2:30 a.m. and prays until dawn. Then he tries

to boost beer sales.

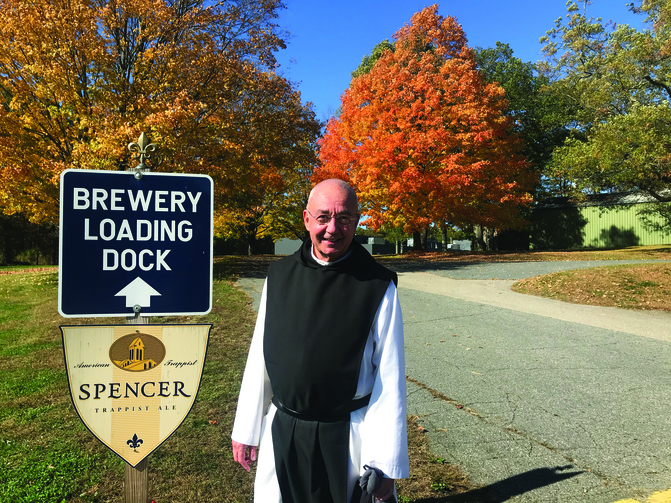

The 69-year-old monk runs Spencer Brewery, America’s first and only Trappist beer-maker, at St. Joseph’s Abbey near Boston, combining modern capitalism with ancient religious practice and revealing the frailties of both the dollar and the divine.

With sales stagnating in a crowded craft beer market, Father Isaac, a former hermit, has summoned his inner Jack Welch. He has had to fire people, master modern analytics and learn jargon like “key performance indicators.” (“It’s sort of like confession. It’s about revealing the truth of what’s going on.”) He has brought in consultants and invited Harvard Business School to carry out a study. Four times a year, he travels to Europe on business.

The 69-year-old monk runs Spencer Brewery, America’s first and only Trappist beer-maker, at St. Joseph’s Abbey near Boston, combining modern capitalism with ancient religious practice and revealing the frailties of both the dollar and the divine.

With sales stagnating in a crowded craft beer market, Father Isaac, a former hermit, has summoned his inner Jack Welch. He has had to fire people, master modern analytics and learn jargon like “key performance indicators.” (“It’s sort of like confession. It’s about revealing the truth of what’s going on.”) He has brought in consultants and invited Harvard Business School to carry out a study. Four times a year, he travels to Europe on business.

Father Isaac must follow the wishes of his own community of 54 brethren, not all of them beer lovers.

There are also loans to pay off and, most important, aging monks to care for. The monastery declined to discuss finances with me, but it aims to produce 10,000 barrels of beer a year within 10 years. (By comparison, Dogfish Head, a major Delaware-based craft brewer, brews around 200,000 barrels a year.) Each Spencer barrel is sold for around $300, according to distributors. That would be around three million dollars a year in revenue. Currently, they are shipping around half that amount. The brewery is on monastic grounds; if it fails, selling the business to non-monks is not an option.

Like any good chief executive officer, Father Isaac trumpets his corporate slogan—“Pair with family and friends”—and his employees: “We have a really lean team.” He is also revving up media exposure, which is why he invited me for a two-day visit. When I covered Belgian beer for The Wall Street Journal, monasteries were never this open to reporters.

While walking the corporate walk, Father Isaac must strive to live a life that is, according to his monastic vocation, “ordinary, obscure and laborious.”

Running a brewery “is an incredibly steep learning curve,” the gentle, moon-faced priest told me when I visited on a bright day in October. The hours of prayer before dawn strengthen him for work: “If I take care of that part of life, I have the peace to live in my corner of the business world. If I can do the business out of that framework, something good is happening to me.”

Running

a brewery “is an incredibly steep learning curve,” the gentle,

moon-faced priest told me when I visited on a bright day in October.

A Centuries-Old Tradition

The name Trappists, one of the strictest orders in the Catholic Church, is a nickname for the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, founded in La Trappe, France, in the 1660s. They follow the Rule of St. Benedict, written in the sixth century, and pray seven hours a day.Like any family, Catholic monks need income for food, shelter, health care, and the local charities they support. In addition, their per capita cost is rising, as communities age and vocations to the monastic life decline, meaning there are fewer able-bodied monks left to work. Sources of income can vary: The world’s 169 Trappist communities make coffee, fudge, fruitcakes, jams, cheese, bread and even clothes. (Only 12 brew beer.)

The world’s 169 Trappist communities make coffee, fudge, fruitcakes, jams, cheese, bread and even clothes.

The origins of St. Joseph’s Abbey are in the French Revolution. In 1789, rebels bent on destroying both throne and steeple torched churches and monasteries, confiscating buildings, art and furniture.

Men and women religious scattered, heading to Belgium, Switzerland and other neighboring countries, as well as to the New World. In 1825, one band of brothers made it to Nova Scotia, Canada, where they farmed corn. After membership dwindled, the community moved to Rhode Island, and then, in 1950, to where it is now: Spencer, Mass., an hour’s drive west of Boston. The monastery earned a living at first by making vestments for priests and jellies and jams.

Meanwhile, in Belgium, surviving Trappist communities rebuilt their crumbling walls. To raise money, they brewed, as their forefathers had done in medieval Europe, where beer was safer than water and integral to secular and religious culture. They had no rules against drinking—those were for Protestants. Initially, their beer was mainly sold locally, but in Europe after the Second World War, sales took off.

I was born in Brussels in 1977, and by the time I started drinking beer in the mid-1990s, the Trappists reigned supreme in a beer-crazy nation. My favorites were Chimay, Orval and Rochefort, magical elixirs, dry and fruity, brewed masterfully with malted barley, hops and yeast. The popularity expanded across the ocean, and some of the monasteries set up distribution networks around the United States. I have found Chimay in bars in Ohio.

Monks in other countries have taken notice, with Trappists in the Netherlands (Zundert), Austria (Engelszell), England (Mount Saint Bernard) and Italy (Tre Fontane) launching breweries to sustain their abbeys.

In 2000 the abbot at St. Joseph’s decided he needed to secure a stronger financial future for the monastery. “Self-support has been an important part of monastic life since the beginning,” Damian Carr, the monastery’s current abbot, told me. “We need as much money to support ourselves as any family would.” In particular, the aging of the community, combined with the rising cost of American health care, is challenging. An advisory group of non-monks, including business leaders and academics, concluded that more revenue was needed.

They ended up with beer “by process of elimination,” said Father Isaac. “It certainly wasn’t where we started. The typical thing would be to make more of what you’re doing to support yourselves.” At Spencer, that meant jams and jellies. “But we’re a niche player in a very mature market”—so those did not offer much opportunity for growth, and would not be a promising investment.

Their other market, for priestly vestments, was also shrinking. “Our main customer has been Catholic priests, and in the last 30 years, the Catholic priest population has decreased by tens of percentages,” said Father Isaac. They looked at wind turbine electrical production. The Federal Aviation Administration ruled out their preferred location because it was on the flight pattern of a local airport.

A second location suffered from weak wind. Finally, somebody suggested a brewery. The advisory board was skeptical. But after they tried a test beer, they liked it and approved the project.

But first, they needed a blessing—and some technical help—from Belgium.

The monks at Spencer ended up with beer “by process of elimination,” said Father Isaac. “It certainly wasn’t where we started."

Beer Barons

Belgian monks set up the International Trappist Association in 1997 to protect and market their brand. Commercial breweries without any religious affiliation were making so-called “abbey” beers, and the Belgian monks wanted their brews marked as authentic. They retained lawyers and threatened to sue imitators. Only the I.T.A. can authorize the placement of the Trappist hexagonal logo on beer and other products.

In February 2010 Father Isaac and another monk flew to Zaventem airport outside Brussels. On that first trip, they took a wrong turn and got lost. “We first went to Westmalle, Achel, Westvleteren; probably Chimay was next, then Orval, Rochefort,” said Father Isaac.

The Belgian monks were skeptical. “They were concerned we would try to become the American Trappist Bud,” said Father Isaac. “In other words, they worried we would not appreciate what they were doing, and that some had spent more than a century growing.” (The I.T.A. did not return emails seeking comment for this article.)

After two years of “shuttle diplomacy,” the Belgian monks approved the project, but recommended that Spencer build a state-of-the-art brewery and only make one kind of beer during its first five years. In 2012, Spencer joined the I.T.A.

Belgium is home to six of the world’s 12 Trappist breweries, including the top-rated Chimay, Orval, Achel, Rochefort, Westmalle and Westvleteren.

An Unlikely Place for a Brewery?

St. Joseph’s Abbey is spread over 2,000 acres, on slopes covered with bright meadows and forests of oak, maple and pine. The peace and beauty are stunning. “The Irish like to say there are places where the boundary between heaven and earth is thin,” said Father Isaac. “It doesn’t matter who you are, if you’re a believer or not. When you’re in that space, you know it’s a special space. God has a way of touching people in that space. You can’t create a thin space. Spencer is a thin space. We’re just the caretakers.”When I first arrived in a rental car from Logan Airport, an 87-year-old monk from Louisiana named Gabriel Bertoniere gave me a tour. He has lived at the monastery since 1952, when he arrived as an English major from Harvard, part of a wave of young men inspired by the writings of Thomas Merton, perhaps the most famous Trappist. Father Gabriel approves of the brewery, even if he does not consume its products. “I’m more of a wine guy,” he said.

The brewery lies beyond the chapel and cloisters, a boxy factory adjacent to a tranquil pond. The monastery will not disclose the cost of operations, but it is very modern, with automated machines that require only a handful of workers.

Everything is top-of-the-line. Bottling lines come from Italy, brewing gear from Germany. Thicker bottles designed to withstand higher fermentation pressures are imported from Belgium. Hops come from the western United States and Germany, malts from the United States, Germany, Canada, the Czech Republic and Canada.

On bottling day—usually Thursday—a couple dozen monks come to help out. On other days, Father Isaac and a few assistants can manage the entire high-tech brewery on their own. “The project was designed to be as automated as possible in this market,” said Brother Michael Rzasa, a former mortician from Johnstown, Pa., who became a monk seven years ago.

St.

Joseph’s Abbey is spread over 2,000 acres, on slopes covered with

bright meadows and forests of oak, maple and pine. The peace and beauty

are stunning.

A Rough Start

In 2013, the brewery launched Spencer Trappist Ale, a 6.5-percent alcohol golden ale. (The average alcohol content of most commercial American beers is 4.5 percent.) Beer websites describe the beer as a “Belgian pale ale.” That’s wrong, according to Father Isaac. “It’s sui generis,” he said, adding: “The right way to describe it is that it’s brewed to have the color of the sunrise on Nauset Beach on Cape Cod on the third Monday of September.” The beer is good—peachy and refreshing—and I recommend drinking it if you can find it.The beer critic Owen Ogletree, in a review for The Beer Connoisseur, called the beer “elegant” and said it “produces restrained aromas of fruity Belgian esters, banana, allspice, nutmeg, vanilla and light tropical fruit allusions.” The beer, he concluded, “ranks as a respectable example of a graceful style of ‘everyday’ beers enjoyed by many Trappist monks.”

Spencer now sells around nine different types of beer, including The Monkster Mash, a pumpkin-spiced ale.

“Unfortunately, Trappist ales are not as popular in America as they once were,” Mr. Ogletree wrote me in an email. “American craft beer geeks seem to be looking for anything that is not classic. Fruit-puree sour beers, two-dimensional kettle soured ales, hazy I.P.A.s sweetened with loads of lactose, and dessert-like pastry stouts are all the rage—along with anything that makes the beer not taste like beer but more like candy or breakfast cereal from childhood.”

The Belgians have been surprised by Spencer’s troubles. They had thought the American beer market was infinite. The solution, Spencer decided, was to diversify. “Starbucks doesn’t have one kind of coffee,” said Father Isaac. Mindful of changing tastes, Spencer introduced other beers, including an imperial stout and an I.P.A.

Spencer now sells around nine different types of beer, including The Monkster Mash, a pumpkin-spiced ale.

The beer that was the hardest for the I.T.A. to accept was the pilsner, a classic light table beer with roots in Germany and the Czech Republic. Trappist monasteries had been overtaken by Nazi troops during the Second World War. “The concern was that it was going to cheapen the brand,” said Father Isaac. “There was animated discussion. Basically, the message was, ‘it’s the German invasion all over again, coming from America.’” Finally, the chair of the meeting tells everyone: “Let’s stop and just drink the beer.” They liked the beer. “They asked us never to export it to Europe.”

Monky Business

Besides reckoning with a saturated beer market, Spencer also faced other hurdles, including a distributor that pulled out of its agreement without warning. After the initial missteps, “we didn’t really have a plan B, so we just picked up the pieces,” said Father Isaac.Last year he invited Harvard Business School students to study the brewery’s business strategy. Among their conclusions: Use analytics to target specific markets and zip codes, and improve its sales and marketing. “Higher level sales leadership is essential to grow the business to the next level,” they said.

Father Isaac called a consultant with experience importing Belgian beers. “We evaluated their sales team,” James Williams, the managing partner at Edge Beverage Consulting, told me. “We decided it would be good to start with a new sales team.”

Mr. Williams and his team also instituted key performance indicators, where salespeople defend their performance to their bosses. That was a new one for Father Isaac.

“We’re trying to refound our economy, keep the monastery going,” Father Isaac said. “That’s a big deal.”

If you want to drink the beer while you’re visiting, you have to hop over to the Black and White Grille, a pizza, nachos and sports bar up the road. By contrast, when I visited Orval in Belgium on a retreat in 2017, the monks served their beer with lunch.

On a walk outside, a car with tourists made a looping approach to the brewery. Father Isaac waved at them. “We have to tell people to turn around and leave,” he said. “Unless they’re from far away. Sometimes we get people from Belgium. I welcome them in.”

Father Isaac, who is from upstate New York and once spent 18 months as a hermit in the Arizona desert, never received any formal education in business. “My father used to tell me he wanted me to go into business and make a lot of money,” he said. “I said ‘I don’t care about money.’”

Now, his calling dictates that he must not only care about money—he must make it. “The beer market is a really tough market because there are so many, and there are a lot of good beers,” he said, sounding with every word more like a C.E.O. and less like a monk. “So what’s really essential is we don’t brew for ourselves. We brew for the consumer. But your beer has to come from who you are. So it’s really important to get a real handle on your identity in the brew world and then really create from that center.”

And where is God in all this? Father Isaac prays while he works. “You’re mindful of work. You remember to remember.” He called the brewery a 100-year project. “If it doesn’t work out,” he said, “we’ve done our best with the best available information.”

It is appropriate that the work is hard, he added. “We’re trying to refound our economy, keep the monastery going,” he said. “That’s a big deal.”

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “The Secret Business Life of Monks,” in the December 9, 2019, issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment