The Secretive Family Making Billions From the Opioid Crisis

You’re aware America is under

siege, fighting an opioid crisis that has exploded into a public-health

emergency. You’ve heard of OxyContin, the pain medication to which

countless patients have become addicted. But do you know that the

company that makes Oxy and reaps the billions of dollars in profits it

generates is owned by one family?

Oct 16, 2017

The newly installed Sackler Courtyard at

London’s Victoria and Albert Museum is one of the most glittering places

in the developed world. Eleven thousand white porcelain tiles, inlaid

like a shattered backgammon board, cover a surface the size of six

tennis courts. According to the V&A’s director, the regal setting is

intended to serve as a “living room for London,” by which he presumably

means a living room for Kensington, the museum’s neighborhood, which is

among the world's wealthiest. In late June, Kate Middleton, the Duchess

of Cambridge, was summoned to consecrate the courtyard, said to be the

earth's first outdoor space made of porcelain; stepping onto the ceramic

expanse, she silently mouthed, “Wow.”

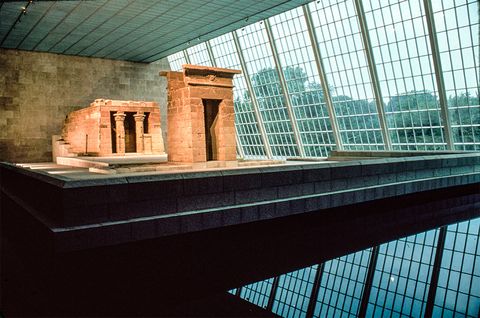

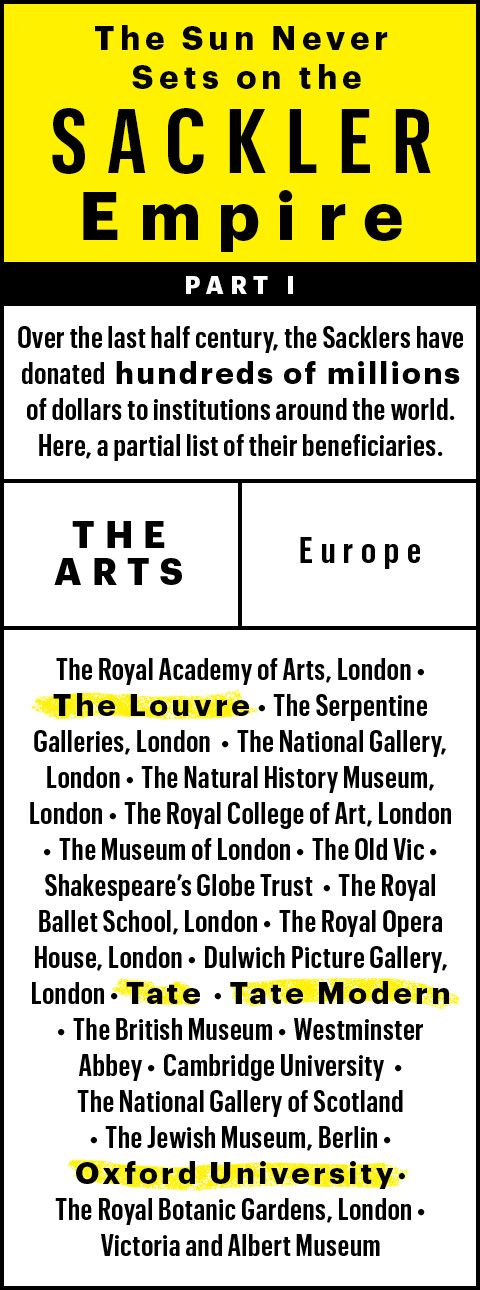

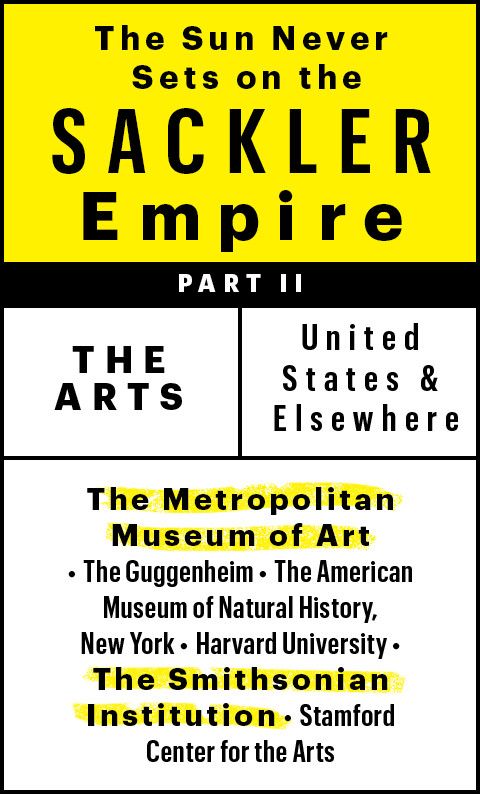

The

Sackler Courtyard is the latest addition to an impressive portfolio.

There’s the Sackler Wing at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, which

houses the majestic Temple of Dendur, a sandstone shrine from ancient

Egypt; additional Sackler wings at the Louvre and the Royal Academy;

stand-alone Sackler museums at Harvard and Peking Universities; and

named Sackler galleries at the Smithsonian, the Serpentine, and Oxford’s

Ashmolean. The Guggenheim in New York has a Sackler Center, and the

American Museum of Natural History has a Sackler Educational Lab.

Members of the family, legendary in museum circles for their pursuit of

naming rights, have also underwritten projects of a more modest

caliber—a Sackler Staircase at Berlin’s Jewish Museum; a Sackler

Escalator at the Tate Modern; a Sackler Crossing in Kew Gardens. A

popular species of pink rose is named after a Sackler. So is an

asteroid.

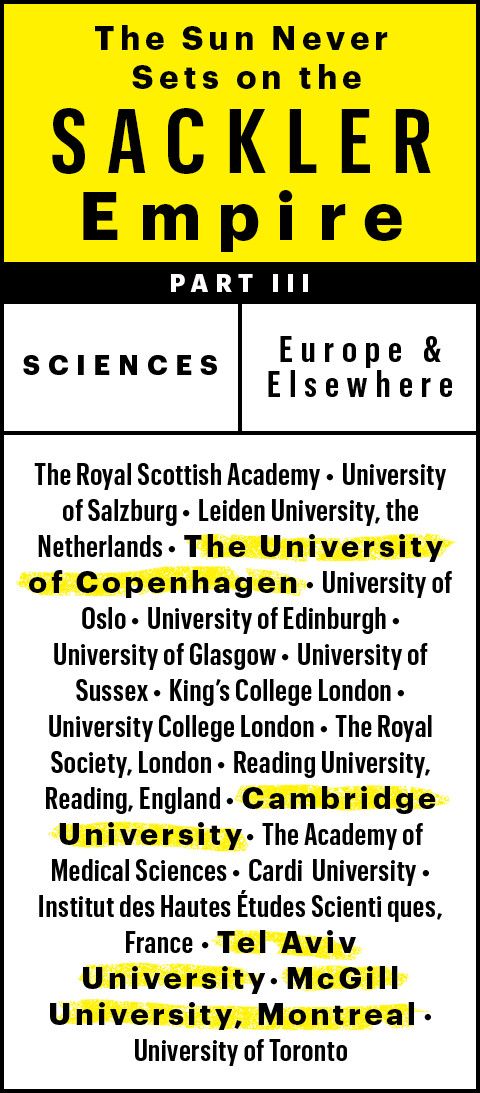

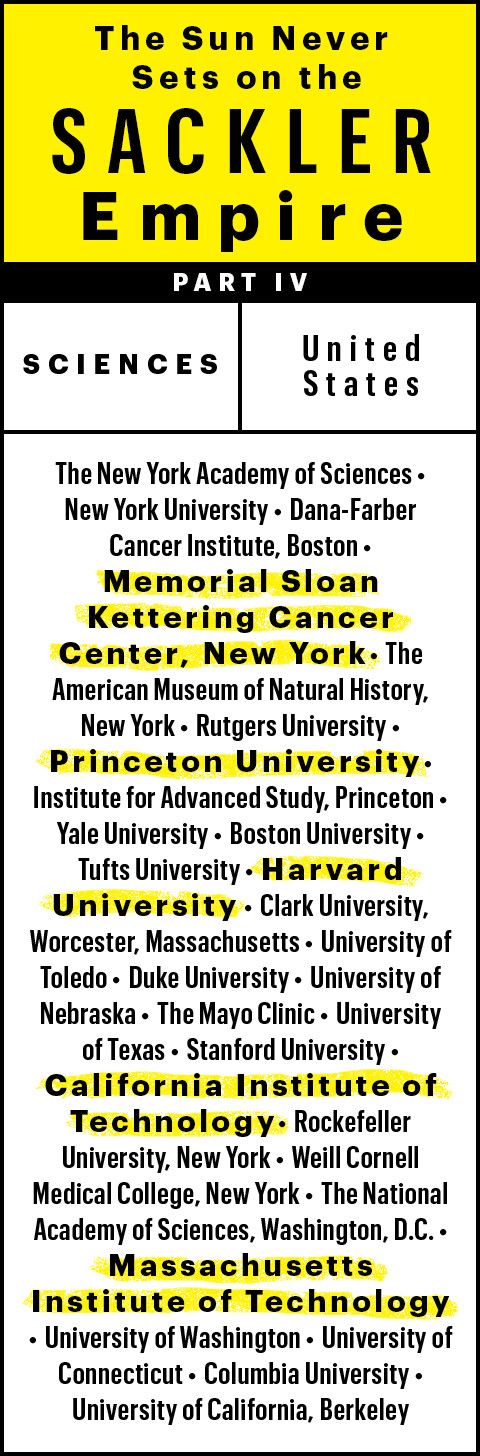

The Sackler name is no less prominent among the

emerald quads of higher education, where it’s possible to receive

degrees from Sackler schools, participate in Sackler colloquiums, take

courses from professors with endowed Sackler chairs, and attend annual

Sackler lectures on topics such as theoretical astrophysics and human

rights. The Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science supports research on

obesity and micronutrient deficiencies. Meanwhile, the Sackler

institutes at Cornell, Columbia, McGill, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Sussex, and

King’s College London tackle psychobiology, with an emphasis on early

childhood development.

The Sacklers’

philanthropy differs from that of civic populists like Andrew Carnegie,

who built hundreds of libraries in small towns, and Bill Gates, whose

foundation ministers to global masses. Instead, the family has donated

its fortune to blue-chip brands, braiding the family name into the

patronage network of the world’s most prestigious, well-endowed

institutions. The Sackler name is everywhere, evoking automatic

reverence; the Sacklers themselves, however, are rarely seen.

The descendants of Mortimer and Raymond Sackler, a

pair of psychiatrist brothers from Brooklyn, are members of a

billionaire clan with homes scattered across Connecticut, London, Utah,

Gstaad, the Hamptons, and, especially, New York City. It was not until

2015 that they were noticed by Forbes, which added them to the

list of America’s richest families. The magazine pegged their wealth,

shared among twenty heirs, at a conservative $14 billion. (Descendants

of Arthur Sackler, Mortimer and Raymond’s older brother, split off

decades ago and are mere multi-millionaires.) To a remarkable degree,

those who share in the billions appear to have abided by an oath of

omertà: Never comment publicly on the source of the family’s wealth.

That may be because the greatest part of that $14 billion fortune tallied by Forbes

came from OxyContin, the narcotic painkiller regarded by many

public-health experts as among the most dangerous products ever sold on a

mass scale. Since 1996, when the drug was brought to market by Purdue

Pharma, the American branch of the Sacklers’ pharmaceutical empire, more

than two hundred thousand people in the United States have died from

overdoses of OxyContin and other prescription painkillers. Thousands

more have died after starting on a prescription opioid and then

switching to a drug with a cheaper street price, such as heroin. Not all

of these deaths are related to OxyContin—dozens of other painkillers,

including generics, have flooded the market in the past thirty years.

Nevertheless, Purdue Pharma was the first to achieve a dominant share of

the market for long-acting opioids, accounting for more than half of

prescriptions by 2001.

According to the Centers for Disease Control,

fifty-three thousand Americans died from opioid overdoses in 2016, more

than the thirty-six thousand who died in car crashes in 2015 or the

thirty-five thousand who died from gun violence that year. This past

July, Donald Trump’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the

Opioid Crisis, led by New Jersey governor Chris Christie, declared that

opioids were killing roughly 142 Americans each day, a tally vividly

described as “September 11th every three weeks.” The epidemic has also

exacted a crushing financial toll:

According to a study published by the

American Public Health Association, using data from 2013—before the

epidemic entered its current, more virulent phase—the total economic

burden from opioid use stood at about $80 billion, adding together

health costs, criminal-justice costs, and GDP loss from drug-dependent

Americans leaving the workforce. Tobacco remains, by a significant

multiple, the country’s most lethal product, responsible for some

480,000 deaths per year. But although billions have been made from

tobacco, cars, and firearms, it’s not clear that any of those

enterprises has generated a family fortune from a single product that

approaches the Sacklers’ haul from OxyContin.

Even

so, hardly anyone associates the Sackler name with their company’s lone

blockbuster drug. “The Fords, Hewletts, Packards, Johnsons—all those

families put their name on their product because they were proud,” said

Keith Humphreys, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University School

of Medicine who has written extensively about the opioid crisis. “The

Sacklers have hidden their connection to their product. They don’t call

it ‘Sackler Pharma.’ They don’t call their pills ‘Sackler pills.’ And

when they’re questioned, they say, ‘Well, it’s a privately held firm,

we’re a family, we like to keep our privacy, you understand.’ ”

To the extent that the Sacklers have cultivated a

reputation, it’s for being earnest healers, judicious stewards of

scientific progress, and connoisseurs of old and beautiful things. Few

are aware that during the crucial period of OxyContin’s development and

promotion, Sackler family members actively led Purdue’s day-to-day

affairs, filling the majority of its board slots and supplying top

executives. By any assessment, the family’s leaders have pulled off

three of the great marketing triumphs of the modern era: The first is

selling OxyContin; the second is promoting the Sackler name; and the

third is ensuring that, as far as the public is aware, the first and the

second have nothing to do with one another.

If

you head north on I-95 through Stamford, Connecticut, you will spot, on

the left, a giant misshapen glass cube. Along the building’s top edge,

white lettering spells out ONE STAMFORD FORUM. No markings visible from

the highway indicate the presence of the building’s owner and chief

occupant, Purdue Pharma.

Originally known as Purdue Frederick, the first

iteration of the company was founded in 1892 on New York’s Lower East

Side as a peddler of patent medicines. For decades, it sustained itself

with sales of Gray’s Glycerine Tonic, a sherry-based liquid of “broad

application” marketed as a remedy for everything from anemia to

tuberculosis. The company was purchased in 1952 by Arthur Sackler,

thirty-nine, and was run by his brothers, Mortimer, thirty- six, and

Raymond, thirty-two. The Sackler brothers came from a family of Jewish

immigrants in Flatbush, Brooklyn. Arthur was a headstrong and ambitious

provider, setting the tone—and often choosing the path—for his younger

brothers. After attending medical school on Arthur’s dime, Mortimer and

Raymond followed him to jobs at the Creedmoor psychiatric hospital in

Queens. There, they coauthored more than one hundred studies on the

biochemical roots of mental illness. The brothers’ research was

promising—they were among the first to identify a link between psychosis

and the hormone cortisone—but their findings were mostly ignored by

their professional peers, who, in keeping with the era, favored a

Freudian model of mental illness.

Concurrent

with his psychiatric work, Arthur Sackler made his name in

pharmaceutical advertising, which at the time consisted almost

exclusively of pitches from so-called “detail men” who sold drugs to

doctors door-to-door. Arthur intuited that print ads in medical journals

could have a revolutionary effect on pharmaceutical sales, especially

given the excitement surrounding the “miracle drugs” of the

1950s—steroids, antibiotics, antihistamines, and psychotropics. In 1952,

the same year that he and his brothers acquired Purdue, Arthur became

the first adman to convince The Journal of the American Medical Association, one of the profession’s most august publications, to include a color advertorial brochure.

In the 1960s, Arthur was contracted by Roche to

develop an advertising strategy for a new antianxiety medication called

Valium. This posed a challenge, because the effects of the medication

were nearly indistinguishable from those of Librium, another Roche

tranquilizer that was already on the market. Arthur differentiated

Valium by audaciously inflating its range of indications. Whereas

Librium was sold as a treatment for garden- variety anxiety, Valium was

positioned as an elixir for a problem Arthur christened “psychic

tension.” According to his ads, psychic tension, the forebear of today’s

“stress,” was the secret culprit behind a host of somatic conditions,

including heartburn, gastrointestinal issues, insomnia, and restless-leg

syndrome. The campaign was such a success that for a time Valium became

America’s most widely prescribed medication—the first to reach more

than $100 million in sales. Arthur, whose compensation depended on the

volume of pills sold, was richly rewarded, and he later became one of

the first inductees into the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame.

As

Arthur’s fortune grew, he turned his acquisitive instincts to the art

market, quickly amassing the world’s largest private collection of

ancient Chinese artifacts. According to a memoir by Marietta Lutze, his

second wife, collecting, exhibiting, owning, and donating art fed

Arthur’s “driving necessity for prestige and recognition.” Rewarding at

first, collecting soon became a mania that took over his life. “Boxes of

artifacts of tremendous value piled up in numerous storage locations,”

she wrote, “there was too much to open, too much to appreciate; some

objects known only by a packing list.” Under an avalanche of “ritual

bronzes and weapons, mirrors and ceramics, inscribed bones and archaic

jades,” their lives were “often in chaos.” “Addiction is a curse,” Lutze

noted, “be it drugs, women, or collecting.”

When Arthur donated his art and money to museums,

he often imposed onerous terms. According to a memoir written by Thomas

Hoving, the Met director from 1967 to 1977, when Arthur established the

Sackler Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to house Chinese

antiquities, in 1963, he required the museum to collaborate on a

byzantine tax-avoidance maneuver. In accordance with the scheme, the

museum first sold Arthur a large quantity of ancient artifacts

at the deflated 1920s prices for which they had originally been

acquired. Arthur then donated back the artifacts at 1960s

prices, in the process taking a tax deduction so hefty that it likely

exceeded the value of his initial donation.

Three years later, in

connection with another donation, Arthur negotiated an even more unusual

arrangement. This time, the Met opened a secret chamber above the

museum’s auditorium to provide Arthur with free storage for some five

thousand objects from his private collection, relieving him of the

substantial burden of fire protection and other insurance costs. (In an

email exchange, Jillian Sackler, Arthur’s third wife, called Hoving’s

tax-deduction story “fake news.” She also noted that New York’s attorney

general conducted an investigation into Arthur’s dealings with the Met

and cleared him of wrongdoing.)

In 1974, when

Arthur and his brothers made a large gift to the Met—$3.5 million, to

erect the Temple of Dendur—they stipulated that all museum signage,

catalog entries, and bulletins referring to objects in the newly opened

Sackler Wing had to include the names of all three brothers, each

followed by “M.D.” (One museum official quipped, “All that was missing

was a note of their office hours.”)

Hoving said that the Met hoped that Arthur would

eventually donate his collection to the museum, but over time Arthur

grew disgruntled over a series of rankling slights. For one, the Temple

of Dendur was being rented out for parties, including a dinner for the

designer Valentino, which Arthur called “disgusting.” According to Met

chronicler Michael Gross, he was also denied that coveted ticket of

arrival, a board seat. (Jillian Sackler said it was Arthur who rejected

the board seat, after repeated offers by the museum.) In 1982, in a bad

breakup with the Met, Arthur donated the best parts of his collection,

plus $4 million, to the Smithsonian in Washington, D. C.

Arthur's

younger brothers, Mortimer and Raymond, looked so much alike that when

they worked together at Creedmoor, they fooled the staff by pretending

to be one another. Their physical similarities did not extend to their

personalities, however. Tage Honore, Purdue’s vice-president of

discovery of research from 2000 to 2005, described them as “like day and

night.” Mortimer, said Honore, was “extroverted—a ‘world man,’ I would

call it.” He acquired a reputation as a big-spending, transatlantic

playboy, living most of the year in opulent homes in England,

Switzerland, and France. (In 1974, he renounced his U. S. citizenship to

become a citizen of Austria, which infuriated his patriotic older

brother.) Like Arthur, Mortimer became a major museum donor and married

three wives over the course of his life.

Mortimer had his own feuds with the Met. On his

seventieth birthday, in 1986, the museum agreed to make the Temple of

Dendur available to him for a party but refused to allow him to

redecorate the ancient shrine: Together with other improvements,

Mortimer and his interior designer, flown in from Europe, had hoped to

spiff up the temple by adding extra pillars. Also galling to Mortimer

was the sale of naming rights for one of the Sackler Wing’s balconies to

a donor from Japan. “They sold it twice,” Mortimer fumed to a reporter

from New York magazine. Raymond, the youngest brother, cut a

different figure—“a family man,” said Honore. Kind and mild-mannered, he

stayed with the same woman his entire life. Lutze concluded that

Raymond owed his comparatively serene nature to having missed the worst

years of the Depression. “He had summer vacations in camp, which Arthur

never had,” she wrote. “The feeling of the two older brothers about the

youngest was, ‘Let the kid enjoy himself.’ ”

Raymond

led Purdue Frederick as its top executive for several decades, while

Mortimer led Napp Pharmaceuticals, the family’s drug company in the UK.

(In practice, a family spokesperson said, “the brothers worked closely

together leading both companies.”) Arthur, the adman, had no official

role in the family’s pharmaceutical operations. According to Barry

Meier’s Pain Killer, a prescient account of the rise of

OxyContin published in 2003, Raymond and Mortimer bought Arthur’s share

in Purdue from his estate for $22.4 million after he died in 1987. In an

email exchange, Arthur’s daughter Elizabeth Sackler, a historian of

feminist art who sits on the board of the Brooklyn Museum and supports a

variety of progressive causes, emphatically distanced her branch of the

family from her cousins’ businesses. “Neither I, nor my siblings, nor

my children have ever had ownership in or any benefit whatsoever from

Purdue Pharma or OxyContin,” she wrote, while also praising “the breadth

of my father’s brilliance and important works.” Jillian, Arthur’s

widow, said her husband had died too soon: “His enemies have gotten the

last word.”

The Sacklers have

been millionaires for decades, but their real money—the painkiller

money—is of comparatively recent vintage. The vehicle of that fortune

was OxyContin, but its engine, the driving power that made them so many

billions, was not so much the drug itself as it was Arthur’s original

marketing insight, rehabbed for the era of chronic-pain management. That

simple but profitable idea was to take a substance with addictive

properties—in Arthur’s case, a benzo; in Raymond and Mortimer’s case, an

opioid—and market it as a salve for a vast range of indications.

In

the years before it swooped into the pain-management business, Purdue

had been a small industry player, specializing in over-the-counter

remedies like ear-wax remover and laxatives. Its most successful

product, acquired in 1966, was Betadine, a powerful antiseptic purchased

in industrial quantities by the U. S. government to prevent infection

among wounded soldiers in Vietnam. The turning point, according to

company lore, came in 1972, when a London doctor working for Cicely

Saunders, the Florence Nightingale of the modern hospice movement,

approached Napp with the idea of creating a timed-release morphine pill.

A long-acting morphine pill, the doctor reasoned, would allow dying

cancer patients to sleep through the night without an IV. At the time,

treatment with opioids was stigmatized in the United States, owing in

part to a heroin epidemic fueled by returning Vietnam veterans.

“Opiophobia,” as it came to be called, prevented skittish doctors from

treating most patients, including nearly all infants, with strong pain

medication of any kind. In hospice care, though, addiction was not a

concern: It didn’t matter whether terminal patients became hooked in

their final days. Over the course of the seventies, building on a

slow-release technology the company had already developed for an asthma

medication, Napp created what came to be known as the “Contin” system.

In 1981, Napp introduced a timed-release morphine pill in the UK; six

years later, Purdue brought the same drug to market in the U. S. as MS

Contin.

MS Contin quickly became the gold standard for pain

relief in cancer care. At the same time, a number of clinicians

associated with the burgeoning chronic-pain movement started advocating

the use of powerful opioids for noncancer conditions like back pain and

neuropathic pain, afflictions that at their worst could be debilitating.

In 1986, two doctors from Memorial Sloan Kettering hospital in New York

published a fateful article in a medical journal that purported to

show, based on a study of thirty-eight patients, that long-term opioid

treatment was safe and effective so long as patients had no history of

drug abuse. Soon enough, opioid advocates dredged up a letter to the

editor published in The New England Journal of Medicine in

1980 that suggested, based on a highly unrepresentative cohort, that the

risk of addiction from long-term opioid use was less than 1 percent.

Though ultimately disavowed by its author, the letter ended up getting

cited in medical journals more than six hundred times.

As the country was reexamining pain, Raymond’s

eldest son, Richard Sackler, was searching for new applications for

Purdue’s timed-release Contin system. “At all the meetings, that was a

constant source of discussion—‘What else can we use the Contin system

for?’ ” said Peter Lacouture, a senior director of clinical research at

Purdue from 1991 to 2001. “And that’s where Richard would fire some

ideas—maybe antibiotics, maybe chemotherapy—he was always out there

digging.” Richard’s spitballing wasn’t idle blather. A trained

physician, he treasured his role as a research scientist and appeared as

an inventor on dozens of the company’s patents (though not on the

patents for OxyContin). In the tradition of his uncle Arthur, Richard

was also fascinated by sales messaging. “He was very interested in the

commercial side and also very interested in marketing approaches,” said

Sally Allen Riddle, Purdue’s former executive director for product

management. “He didn’t always wait for the research results.” (A Purdue

spokesperson said that Richard “always considered relevant scientific

information when making decisions.”)

Perhaps the

most private member of a generally secretive family, Richard appears

nowhere on Purdue’s website. From public records and conversations with

former employees, though, a rough portrait emerges of a testy eccentric

with ardent, relentless ambitions. Born in 1945, he holds degrees from

Columbia University and NYU Medical School. According to a bio on the

website of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT,

where Richard serves on the advisory board, he started working at Purdue

as his father’s assistant at age twenty-six before eventually leading

the firm’s R&D division and, separately, its sales and marketing

division. In 1999, while Mortimer and Raymond remained Purdue’s co-CEOs,

Richard joined them at the top of the company as president, a position

he relinquished in 2003 to become cochairman of the board. The few

publicly available pictures of him are generic and sphinxlike—a white

guy with a receding hairline. He is one of the few Sacklers to

consistently smile for the camera. In a photo on what appears to be his

Facebook profile, Richard is wearing a tan suit and a pink tie, his

right hand casually scrunched into his pocket, projecting a jaunty

charm. Divorced in 2013, he lists his relationship status on the profile

as “It’s complicated.”

No comments:

Post a Comment